Challenge of the Southern Cross Rally

Challenge… or obsession…

The first Southern Cross Rally was run while I was in my early twenties, at that time an impoverished Uni student with an unhealthy fixation on rallying (rather than studying!). I was an active member of the University Car Club, whose rallying was still very much in the navigational era. However, up in the reading room at the students’ union building, you could find the occasional copy of the English Autocar magazine with a report on a European championship rally.

In Europe, route-charted events were replacing navigational rallies – ‘forest racing’ was being born, and it seemed really exciting. And the Southern Cross was leading Australian rallying in that direction.

I graduated at the end of 1969, found a job, and my second priority for 1970 was to compete in the Southern Cross that year. First priority turned out to be getting married, my wife had a Morris Mini, so that saw us enter the poor little Mini – totally unsuited to long, gravel events – in the 1970 Southern Cross. And just missing out on a class win. The Great Adventure had begun.

That was the start on a 10-year involvement – or possibly, obsession – with the Southern Cross. In 1972 I entered a Galant 1300, re-engined with a 1500cc motor for the 1973 event. In 1975 I entered a Toyota Sprinter, and in 1976 a Mitsubishi Lancer. Finally, in 1978, I went back to Galants and had my best ever result in a ‘Group 5’ 1700cc version.

In the years that I didn’t compete (i.e. couldn’t afford to!) I was usually involved in some way; occasionally assisting with running the event, at other times assisting other competitors.

For a mere clubman driver – and not a very talented one at that – the Southern Cross represented the ultimate challenge in Australian rallying. It provided the opportunity to compete against overseas stars, whose cars (and teams) were quite inspirational in terms of preparation standards and general professionalism. More than that, it provided the ordinary clubman driver with the opportunity to become a “professional” rally driver for four days each year. For four days, all your waking and sleeping activities were geared to rallying. You got to rub shoulders with the ‘works’ teams. It was a fantastic break from a consuming career job – for four days you didn’t have time to even think about work.

For four days, you lived the ultimate challenge in Australian rallying.

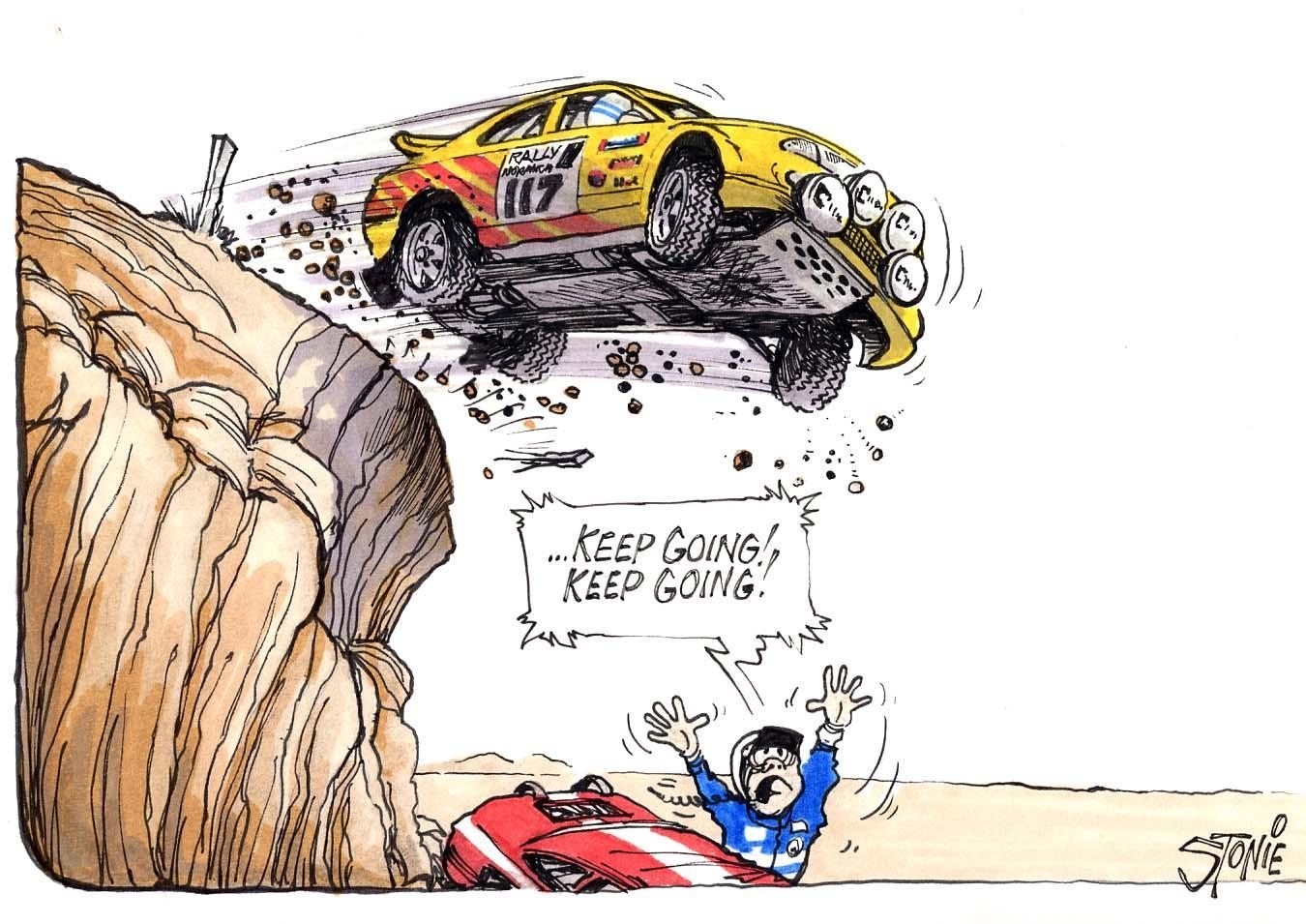

For those four days, you threw care to the winds. Every gear change at maximum revs – the fact that you had maybe another 1500 kilometres to finish the event never caused you to wonder whether to take the strain off the car.

One of my enduring memories is of a point twenty kilometres from the start of the legendary ‘Horseshoe’ stage, in the middle of the night, when the thought crossed my mind as I approached maximum revs:

“If the engine goes ‘POP!’, I’ve got absolutely no idea what I’ll do. I’ve got no idea how far back it is to ‘civilisation’, how I would get help, or how I would get the car back to Canberra.”

But still I took the engine up to maximum revs for that gear-change, and the next, and the next ….

Perhaps the Southern Cross was more than an “opportunity”, or more than a “challenge” – perhaps it was more like an obsession. I can recall that, after completing each Southern Cross, I would immediately start planning for the next.

Usually this involved some extremes in thinking. For example, I would wonder whether I should take a strategic decision to abandon my participation in club-level rallying for the next year, so that the rally car would be in optimum condition for the toughest event of the Australian calendar.

A significant factor in the aura of the Southern Cross was that it immediately followed Australia’s pre-eminent touring car race at Bathurst each October. At that time, Australia had a concentrated week of top-level motor sport. Indeed, some of the leading drivers were so versatile (and talented) that they raced at Bathurst one weekend, then lined up for the Southern Cross three days later. However, even if you weren’t at this level of competition, you could watch Bathurst on TV to get “motivated” for the Southern Cross, so you still had your full week of motor sport.

The final component of the “obsession” was the quality of results; mine were fairly mediocre. Most of the time I finished in the mid-twenties, usually after suffering mechanical difficulties (as did most Southern Cross competitors!). One year I picked up a class win, another a second in class, and one year I failed to finish (broken alternator). My ultimate objective was to finish in the first ten place-getters; if you could crack the first ten you were really somebody! And I failed to ever reach my objective. In my final year of Southern Crosses (1978) I came 11th! Two years later, the Southern Cross Rally was no more.

In the twenty years after the Southern Cross was abandoned, I came to recognise certain symptoms in myself that are classic “war horse” syndrome. Not just dwelling on the halcyon years, and dreaming of what might have been, “if only”. In the late nineties, there were occasional media reports of entrepreneurial rally directors planning to resurrect the Southern Cross. Like an old war horse, my immediate reaction was “Where do I go? When can I charge?” What do I need to do to ensure I’m involved?

At the turn the century (I always wanted to say that!) I abandoned my focus on “conventional” rallying at state/clubman level, and decided to concentrate instead on ‘historic’ rallies. I wanted to ensure I had a suitable (i.e. eligible) car if the media reports turned into reality. They didn’t, but in 2001 the Victorian Historic Rally Association re-created the “Historic Alpine”, and my “new” (1972 model) car was blooded. I’ve been privileged to drive in a couple of Alpines, although this event has evolved into a classic “forest race” – some might say, replicating the nature of the Alpine during the seventies, in contrast with the much longer, more measured competition of the Southern Cross.

So what of the ‘Cross? Every so often rumours of its resurrection have emerged, but ultimately these rumours have all ebbed and vanished. Perhaps society’s evolution over the last thirty years is an insuperable obstacle to running a rally anything like the old ‘Cross?

There are now four times as many cars on the roads of NSW as there were in 1970. Large areas of NSW state forests have been turned over to national parks, which prohibit rallying. Several large towns in the traditional Southern Cross territory have extended their boundaries, encroaching on what we regarded as “traditional rally country”.

Thanks to the popularity of 4WDs, many more people are driving through forests these days on recreational jaunts. The days of rallying one’s street car have long passed, particularly with the development of contemporary safety requirements and conflicting civil registration requirements.

Perhaps most significantly of all, rallying itself has evolved from what, in the late sixties and seventies was an adventure sport, to what is now regarded as an “extreme sport”.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the respected rally drivers were those could drive quickly yet carefully, typically over long distances and for long periods, with the expectation of a high probability of finishing the rally.

Rallying now is characterised by very short special stages, guidance from pace-notes, opportunities to repair the car after every stage, and very little night driving. However, competitors require the commitment to use every inch of the road, plus some, and to expect that “offs” may be frequent and, quite possibly, terminal. It is very much an extreme sport: brief, intense, and with a high risk of disaster.

So, for this war horse, perhaps it’s too late to sound the charge. Or, at least, a genuine Southern Cross charge.

So my 40-year obsession is under threat.

You can handle this one of two ways. You can get disappointed, depressed, ruing the passing of the “good old days”, and consequently being avoided by all your former friends. Or you can sit back with a feeling of great self-satisfaction, because you were there. You had the opportunity to be part of something magic, something that’s probably not going to happen again, and you’re very privileged.

It doesn’t matter if you competed, or helped in some way as an official or service crew member, in one Southern Cross or ten – you’re part of a very select group.

I’m in the second camp; I call it “caring for my obsession”.

Written by Bob Moore